The devastating defeat of Ohio Issue 3 has been interpreted by some observers as a victory against the corporatization of marijuana. Bill Maher opined on his HBO show that marijuana was “The one seed Monsanto hasn’t [messed] with” and “Can’t the hippies control it a while before RJ Reynolds takes over?” Willie Nelson spoke out against the advance of so-called “Big Marijuana” monopolizing the weed industry.

The implication is that if a marijuana legalization plan doesn’t sufficiently open up the marijuana growing and selling to “the little guy”, prohibition should be allowed to continue. Corporate-controlled marijuana has been elevated to a greater bogeyman status than the police who strip search and kill people over the smell of marijuana.

This economic re-framing of the marijuana legalization debate restricts the options for marijuana legalization. The Ohio model was based on a suggested framework from a report written by the RAND Corporation for the state of Vermont, which wanted to know all the possible ways marijuana laws could be reformed.

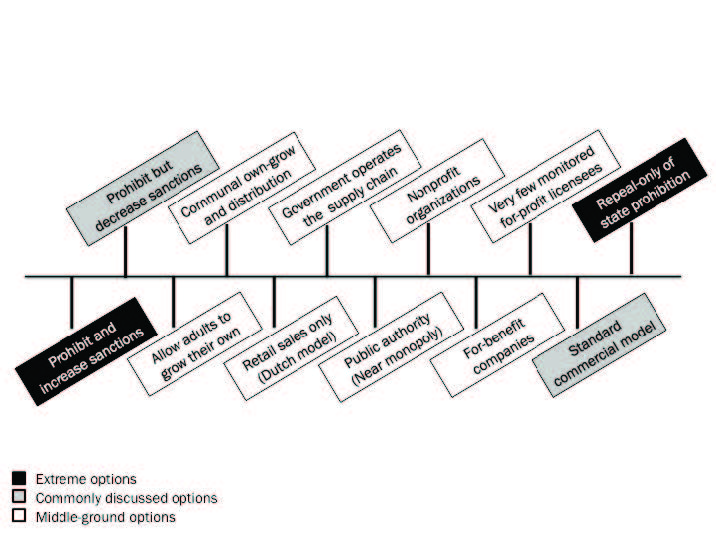

RAND came up with something of a spectrum of twelve marijuana legalization options, from the most-repressive to the most-liberal. “Extreme Options” were to double-down on the Drug War (“prohibit and increase sanctions”) on the repressive side and to complete Deregulation (“repeal-only of state prohibition”) on the liberal side.

Then in the “Commonly-Discussed Options”, RAND talks about Decriminalization (“prohibit but decrease sanctions”) on the repressive side versus Regulate Like Alcohol models that are already in place in four states (“standard commercial model”).

Of those four options, capitalist reformers certainly won’t support more Drug War and should support decriminalization. Complete repeal of prohibition without some commercial regulation seems unlikely. So for that one “standard commercial model”, what will qualify as “standard” for capitalist marijuana advocates? How many grow licenses must be made available and how low must the application and licensing fees be to not be interpreted as an oligopolistic cash grab like Ohio’s Issue 3?

Next in the “Middle-Ground Options”, RAND discusses eight other possibilities for regulating marijuana as a legal product. How many of these options would be vetoed now by capitalist marijuana reformers as “anti-free market”?

Grow and Give (“allow adults to grow their own”) is the system currently in place in Washington DC and was the system in Alaska for decades before their legalization. Adults can cultivate a small amount of marijuana and possess and share it, but there is no commerce allowed in marijuana. Since this isn’t giving the market to anybody and legalizes the consumers buying from the black market, there shouldn’t be any conflict for capitalist marijuana reformers.

Buyers’ Club (“communal own-grow and distribution”) is a model like the Spanish collectives, which allow consumers to grow in co-operative gardens and sell the marijuana among the members at cost. This model would exemplify the small, artisanal-style grows favored by political left of the capitalist marijuana reformers, but would the business-minded right find it to be an unfair restraint on trade?

Coffee Shops (“retail sales only”) is the Dutch model, where the growing and wholesale distribution of cannabis is still strictly illegal, but the sales of small, personal-use amounts of marijuana are tolerated in well-regulated coffee shops. This model ends the arrests for personal possession and use, but home cultivators and commercial growers remains criminals. Could capitalist marijuana reformers bring themselves to support this scenario?

Government Control (“government operates the supply chain”) would be a system similar to Uruguay, where the government produces and sells all the marijuana, perhaps also including a registration system for marijuana consumers. Capitalist marijuana advocates would be sure to reject such a system, since it would be an actual monopoly.

Public Authority (“public authority – near monopoly”) would have a single government-sanctioned private entity in charge of marijuana production and distribution. This model insulates the state from its employees and agencies being charged with federal law violations. Functionally, however, it would be similar to the government control and monopolistic enough to earn the ire of capitalist marijuana reformers.

Allowing only Non Profit Organizations to grow and distribute marijuana may be one option governments consider to slow the growth and control the marketing of the marijuana industry. Perhaps some capitalist marijuana reformers could accept that growers would at least have those business opportunities available. But perhaps some would oppose this model for its lack of for-profit opportunities.

A compromise between non-profit and for-profit would be to allow For-Benefit Corporations to have sole control of the marijuana cultivation and sales. Twenty-seven states have this sort of corporate structure that allows some profit-making but also incorporates public-benefit considerations. This might be a more palatable option for some capitalist marijuana advocates.

Finally, there is the model just rejected in Ohio, the Structured Oligopoly (“very few monitored for-profit licensees”) where just a few licenses are granted, giving the government closer oversight of just a few regulated entities. Indeed, the ResponsibleOhio campaign explained that benefit to Ohioans in RAND’s own words: “A rogue company could more easily break the rules if it were one of 1,000 licensees than if it were one of just ten.”

This is a war my government declared on me. My enemies are not investors and capitalists. My enemies are cops and drug testers. So I will support every one of the options RAND proposes that moves us further from marijuana prohibition. Sadly, though, it seems there is now a faction of capitalist marijuana reformers who would only accept fewer than half of these options.